search the site

Towards a Cohesive Maritime Security Architecture in the Indian Ocean

Introduction

The Indian Ocean Region is becoming more important in Asia’s shifting security landscape. Once considered a “neglected ocean”,[1] it has become a critical theatre in global geopolitics, with even external players showing heightened interest.[a]

As countries in the region become key stakeholders in the Indian Ocean and beyond, maritime security remains critical. Compounding the challenge are non-traditional threats like maritime terrorism and piracy. Regions bordering South Asia, including the Bay of Bengal and Western Indian Ocean (WIO), are also witnessing a rise in environmental challenges from natural disasters.[2] These factors have heightened the need for stronger maritime security cooperation in the Indian Ocean.

Additionally, the “rise and return”[3] of the Indo-Pacific has positioned the Indian Ocean as a vital sub-strategic theatre in the Indo-Pacific, especially for extra-regional players. As global powers continue to view the Indo-Pacific as a singular strategic theatre for cooperation on economy, trade, and connectivity, the Indian Ocean remains important even for countries without direct stakes in the region.[b] Therefore, the contemporary Indo-Pacific construct draws more attention to the Indian Ocean, particularly from actors historically focused on the Pacific but are now seeking to expand their presence and harness shared opportunities of trade and connectivity.

This brief argues that the region’s security architecture continues to be fragmented due to three key factors: minimal synergy among key actors; lack of political unity; and diverse challenges in various sub-regions across the Indian Ocean. To build a cohesive maritime security structure, the Indian Ocean must be viewed as a singular political entity. Emphasising shared challenges and strengthening institutional mechanisms, such as the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA), is crucial.

Evolving Geopolitics in the Indian Ocean

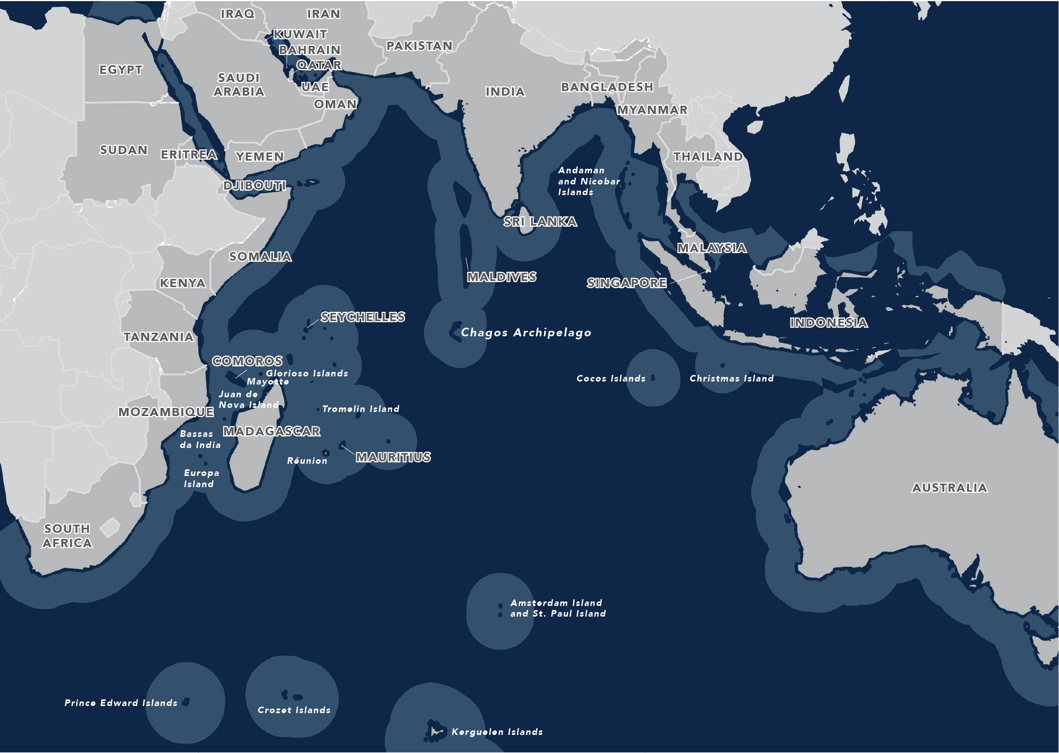

A geopolitical context is essential to map the maritime security architecture in the Indian Ocean, starting with its geographical contours. While the Indian Ocean is viewed as a strategic theatre, the Indo-Pacific has evolved as a strategic construct. Countries thus define the Indo-Pacific’s boundaries differently, according to their national and global interests. The Indian Ocean region, on the other hand, is more consistently defined—geographically, stretching from the western coast of Australia to the Mozambique Channel.[4]

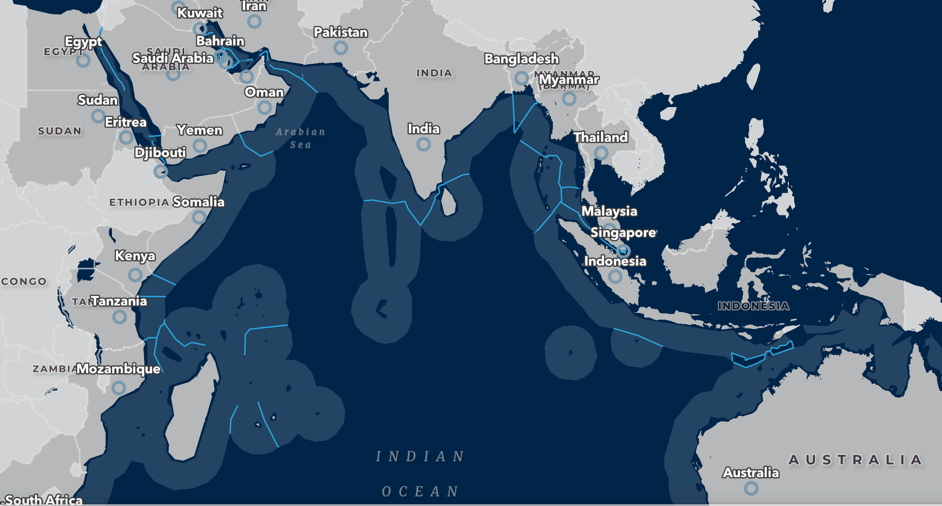

Figure 1: Strategic Map of the Indian Ocean

Source: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace[5]

Historically, the Indian Ocean was a key geography that facilitated European colonial expansion into Asia.[6] Its relevance declined after decolonisation, particularly during the Cold War.[c] After the Cold War, a strategic vacuum emerged in the Indian Ocean, likely due to its fragmented political construct and the lack of any remarkable contestations, regional or global. According to Frederic Grare and Jean Loup-Samaan, it was the twenty-first century economic rise of India and China, along with the rise in the incidence of piracy off the Somalia coast beginning around 2008, that brought the Indian Ocean into the limelight.[7] This phenomenon was driven by both economic and security rationales. As global trade increased with the rise of India and China, the need to secure the region followed. The legacy of the Cold War also left a lasting impact on the geopolitics of the Indian Ocean. Small states in the region leveraged their geography to shape geopolitical dynamics, becoming crucial for global powers seeking to project their influence and power.

A new set of stakeholders has emerged in the Indian Ocean, influencing the region’s maritime security architecture. These actors fall into three categories: major residents powers; major non-resident powers; and small island and littoral countries.[d] Major resident powers such as India, Australia, and more recently France, play a central role due to their substantial capabilities in the economic, security, and political spheres. Non-resident powers such as the United States (US), China, Japan, and South Korea have also become significant actors.[e] The US maintains a historical military presence through its base in Diego Garcia,[8] while China is expanding its naval presence in the region.[9] The third category of small and littoral states such as Sri Lanka, Maldives, and Djibouti, have limited economic and military capabilities but are gaining political influence by leveraging their strategic locations. These states are becoming important sites of competition among global powers. Additionally, actors such as the Gulf countries, Canada, and African countries have interests in the Indian Ocean though they play a marginal role in shaping the overall regional maritime security architecture.

While these actors continue to pursue their own national interests in the Indian Ocean, a broader maritime security architecture is emerging, shaped by complex strategic and security partnerships. As the Indian Ocean evolves into a vital and singular strategic theatre, countries are identifying common interests that underpin their cooperation on key issues, particularly security. Security cooperation has become a central element of Indian Ocean geopolitics, driving the development of this broader maritime security framework. Various stakeholders are actively working to enhance cooperation based on shared maritime interests, with these mechanisms unfolding at multiple levels. States continue to cooperate on bilateral, minilateral, and multilateral levels. While bilateral maritime security efforts typically focus on shared regional concerns, minilateral and multilateral cooperation are shaping the broader security architecture in the Indian Ocean.

Key Actors in the Indian Ocean

Grare and Samaan (2022) describe the Indian Ocean’s architecture as “multipolar”.[10] Instead, new actors, including those from Africa and West Asia, have emerged as contributors after long being marginal. The proliferation of these new actors is driven by their growing articulations of interests in the region. The following paragraphs highlight some of the key players and their stakes.

India

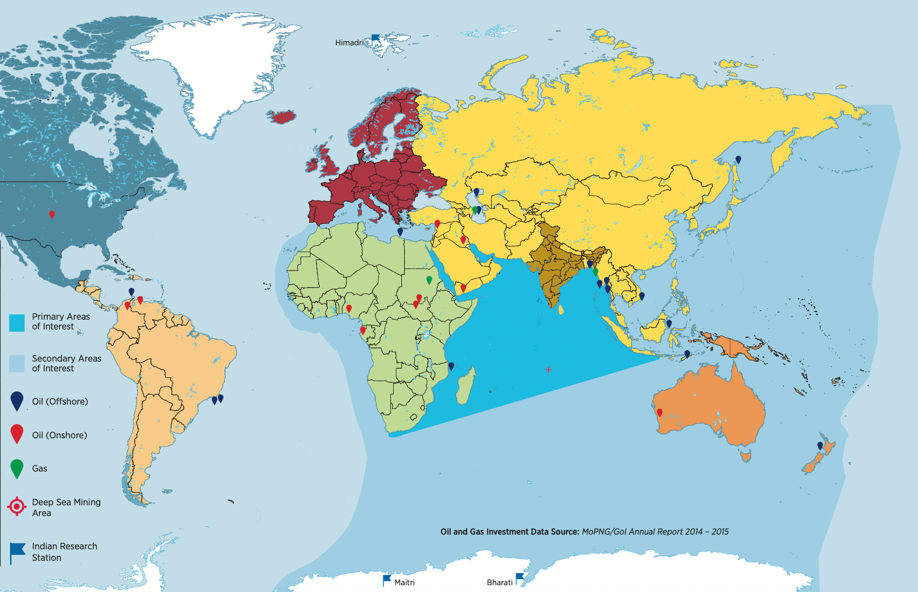

The Indian Ocean is crucial for India, with its geography making it the region’s most significant actor. The region’s security dynamics have thus become central to India’s strategic thinking.[11],[12] India’s rise as a security actor is supported not only by its geographic position but also by its growing naval capabilities and economic heft. The Indian Ocean remains vital for India’s core interests, including trade and the extraction of marine and mineral resources.[13] For this, it is vital that New Delhi ensures the protection of its vital sea lines of communication (SLOCs).

India’s role in the broader maritime security architecture of the Indian Ocean is also tied to its position as a net security provider in the region and wider Indo-Pacific.[14] With the region vulnerable to non-traditional maritime security challenges such as those brought about by climate change, maritime terrorism, and piracy, India plays a vital role in combatting these threats, not only for its own security but also that of its maritime neighbours.[15] Over time, India’s role has evolved from a ‘security provider’ to a ‘first responder’ or ‘preferred security partner.’[16]

Figure 2: The Indian Ocean: India’s Primary Area of Interest

Source: Indian Navy[17]

United States

Since the end of the Cold War in 1991, the US has remained a key security actor in Asia, though the Indian Ocean has historically been a secondary strategic theatre compared to Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia.[18] Though not geographically located in the region, the US has increasingly articulated its maritime interests in the Indian Ocean,[19] driven by its role in maintaining the post-Cold War global order. Washington is also deeply engaged with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as a key security partner. While Washington’s interests have remained in the Pacific, with extensive security partnerships in the region, the Indian Ocean is gaining increased attention. Arguably, China’s economic rise and growing influence in Asia have been key factors in shaping US engagement.[20]

US policy towards Asia has shifted based on the evolving geopolitical dynamics and its changing interests. During the Cold War, US strategy was guided by the ‘arc of crisis’ concept, later transitioning to the ‘Pivot to Asia’ in the 2010s. In the maritime context, US involvement was initially centred on the ‘Asia-Pacific,’ excluding much of the Indian Ocean.[21] Later, with the advent of the Indo-Pacific, endorsed by successive US leaders, attempts have been made to formally expand the US’s strategic focus into the Indian Ocean. China’s expanding naval and political influence in the region remains a key concern, but US interest relies on India to counter Chinese aggression. In the Indo-Pacific context, the US has articulated its willingness to engage India bilaterally and multilaterally as a major defence[22] partner to secure a free and open regional order. Importantly, the US’s growing interest in the Indian Ocean is closely tied to its commitment to the Indo-Pacific. While it remains a player in the Pacific and eastern Indian Ocean, the Western Indian Ocean has been largely excluded from US strategic priorities.[23]

More recently, the US has aimed to strengthen its focus on the Indian Ocean through initiatives like the Indian Ocean Strategic Review Act, 2024, to promote economic interests, secure freedom of navigation, and enhance cooperation with partners such as India, France, and Australia.[24]

Figure 3: USINDOPACOM Area of Responsibility

Source: US Indo-Pacific Command[25]

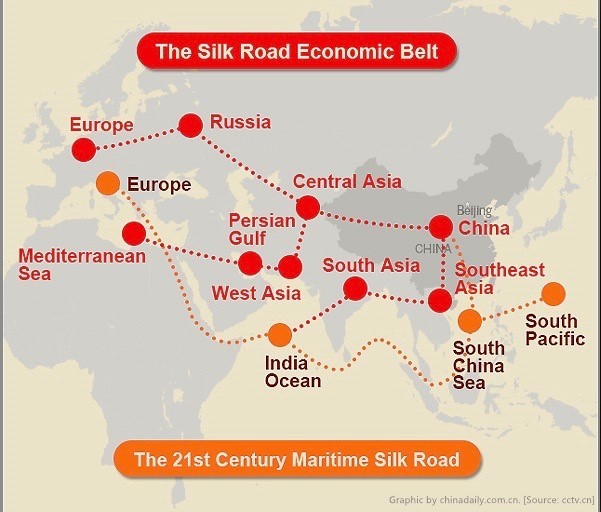

China

China’s emergence as a critical player in global geopolitics has reshaped the security architecture in Asia. While some view China as a revisionist power, seeking to alter the post-Cold War status quo in global order, its ambitions are rooted in recovering from what it calls a ‘century of humiliation’ (1839-1949), and establishing a sphere of influence in Asia.[26] China’s expanding economic and military capabilities underpin its influence beyond its traditional focus. This push into the Indian Ocean is both a strategic extension[f] of its ambitions and a response to its growing energy needs as its economy and population expand.

The West Asia geography is also critical for Beijing’s energy demands[27] and thus considers the maritime route through the Indian Ocean as vital. China’s outlook towards the region is driven by its strategic concerns, including the so-called ‘Malacca Dilemma’—i.e., the fear of a potential blockade by the US, India, and others in the Strait of Malacca.[28] To mitigate this, China is expanding its strategic and military footprint in the region,[29] forging partnerships with Indian Ocean littoral states in South Asia and Africa. This raises concerns about the potential proliferation of Chinese bases across the Indian Ocean.[30]

Figure 4: China’s Silk Road Economic Belt and Maritime Silk Route Initiative

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asian states have traditionally focused on the Pacific, particularly the South China Sea, where they hold influence. However, their geostrategic location between the Indian and Pacific oceans makes them crucial in the geopolitical developments in the Indian Ocean.[32] The gateway between these oceans largely falls under territories belonging to Southeast Asian states, giving them a stake in evolving security dynamics.[33] The ASEAN fosters strong regional consciousness in the Southeast Asia region. Despite challenges from evolving geopolitical regional dynamics, China’s rise, and the Myanmar crisis, maritime cooperation remains strong, and there is a need to diversify and broaden engagements across the Indian Ocean.[34]

ASEAN’s engagement with India enhances its presence in the Indian Ocean, while ASEAN centrality in the Indo-Pacific underscores Southeast Asia’s growing importance in shaping the region’s maritime security architecture. However, by logic of geography, interest, and capabilities, ASEAN countries have bolstered their presence mostly in the Bay of Bengal region. Strategic areas within the Indian Ocean like Western and South Indian Ocean see limited ASEAN presence for several reasons. First, geographically, the ASEAN countries’ exposure in the Indian Ocean is centred around the Bay of Bengal, making it the region where ASEAN is likely to emerge as an important maritime security actor. Second, because ASEAN’s location in the Indian Ocean region is exposed to the Bay of Bengal region, they appear to be placing little emphasis on other sub-geographies in articulating their interests. While the South China Sea remains an important theatre for ASEAN, in the Indian Ocean, the grouping’s political and security compulsions primarily remain in the Bay of Bengal region. Lastly, ASEAN’s military dependence on the US limits its ability to expand its influence beyond the Bay of Bengal.

Figure 5: Southeast Asia in the Indo-Pacific

Source: Asia Society[35]

Australia

Australia has the longest coastline in the Indian Ocean[36] and commands the largest maritime jurisdiction in the region, covering an exclusive economic zone of 6,369,268 square kilometres.[37] Still, Canberra’s strategic thinking is centred on the Pacific Ocean, framing itself primarily as a Pacific Ocean state.[38] However, Australia’s growing engagement with the Indian Ocean has been crucial in shaping its Indo-Pacific outlook. Australia is uniquely situated in Indo-Pacific geopolitics.

Historically, Australia has been dependent on China for economic prosperity, and on the US for security.[39] The shifting geopolitical dynamics in Asia have presented Canberra with a dilemma between economic and security partnerships, exacerbated by the deterioration in China-Australia relations post-COVID-19,[40] compelling Canberra to redefine its role in the Asian geopolitical matrix. The growing salience of the Indo-Pacific, in Canberra’s strategic thinking, presented an opportunity to reduce its dependence on China, while remaining part of the US-led post-Cold War security order in the Asia Pacific.

Notably, the influence of the Western Australian leaders in domestic political dynamics is seen as key factor in this shift.[41] Australia’s engagement in the Indian Ocean, however, is constrained by geography—i.e., its shifting focus on the Indian Ocean is tied to its Indo-Pacific strategy, which responds to geopolitical shifts in Asia.[g] Australia’s definition of the Indo-Pacific geography remains limited to the eastern Indian Ocean. Australia’s role in the broader maritime security architecture of the Indian Ocean thus remains limited.

Figure 6: Australia in the Indo-Pacific

Source: India Foundation[42]

Small Littoral and Island States in the Indian Ocean

Geopolitics in the Indian Ocean involves more than just the global and middle powers. Small littoral and island countries have gained strategic importance in shaping the region’s maritime security architecture.[43] Particularly in South Asia and Africa, these countries have become significant due to shifting geopolitical dynamics. Apart from India, no other big power has geographical leverage in the Indian Ocean. This has positioned small island and littoral countries as key sites of geopolitical competition.

These countries are seeing increased engagement by major powers such as China, the US, and France, all seeking to expand their geopolitical influence. Their strategic locations offer geographical advantages for power projection and access to oceanic trade routes, buffering their heft. This has, in turn, spurred a geopolitical contest with significant maritime security implications in the Indian Ocean. Notably, China’s expanding political and military influence has been aided by Beijing’s growing engagement with these players. Meanwhile, these small littoral and island states have cultivated political agency by using their geographic position as a bargaining tool to secure their national interests. Vulnerable to ecological crises at sea and reliant on external partners for capabilities, economic bandwidth, and security continue to play a role in shaping the maritime security architecture in the Indian Ocean.

Figure 7: Island Countries in the Indian Ocean

Source: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace[44]

Figure 8: Littoral Countries in the Indian Ocean

Source: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace[45]

The Current Indian Ocean Maritime Security Architecture

In the Indian Ocean region, the role of an institutional mechanism in maritime security is complicated by the lack of regional consciousness and political unity. Whereas Europe has the European Union, Southeast Asia has the ASEAN, and Africa, the African Union—the Indian Ocean does not have a similar mechanism that speaks of political coherence. This can be attributed to the vast geographical expanse of the Indian Ocean. For long, states have prioritised a territorial understanding of regionalism, where regional consciousness is built on interconnectedness linked through territorial continuum.

The IORA, created in 1997, serves as an important intergovernmental organisation and remains the only pan-Indian Ocean regional institution. In this regard, IORA could indeed symbolise an “Indian Ocean identity”.[46] First formed as the Indian Ocean Region Association for Regional Cooperation (IOR-ARC) by India and South Africa, IORA has played important role in fostering regional consciousness among Indian Ocean littoral states. At present, IORA has 23 full-fledged members and 12 dialogue partners.[47]

Figure 9: Map of IORA Member Countries

Source: Indian Ocean Rim Association[48]

The Council of Ministers is the highest decision-making body of IORA and has evolved into a key platform to debate and discuss the critical strategic, economic, and security concerns of member states. One of IORA’s primary focus areas is ‘Maritime Safety and Security’.[49] While there is potential of shaping a maritime security agenda in IORA, the group has had limited success in building broader consensus. This is because the dialogue within IORA is more diplomatic in nature, without direct participation from naval forces. Although diplomatic discussions on maritime security can help establish a political roadmap, in IORA’s case, they have been hindered due to the differing political and military perspectives of its member states.

The Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS), conceived in 2008 by India, is another important institutional framework in the Indian Ocean. Unlike IORA, IONS is a forum for maritime cooperation among the navies and coast guards of the member states. At present, IONS has 25 full-fledged members and nine observer nations.[50] The IONS operates through three key working groups— Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief; Maritime Security; and Information Sharing and Interoperability—highlighting its naval orientation. Despite its operational status and the importance of its focus areas, IONS has had limited success in fostering a regional approach to maritime security cooperation.[51] Although it serves as a critical forum, IONS has struggled to consolidate a unified regional strategy to address maritime security challenges in the Indian Ocean.

Figure 10: Participating Members and Observers in IONS

Source: Indian Ocean Naval Symposium[52]

Apart from multilateral regional platforms, the Indian Ocean has witnessed a rise in the number of minilateral groupings where few geographically proximate countries collaborate on maritime security challenges specific to their immediate region.[h],[53],[54] A number of minilateral groupings in the wider Indo-Pacific landscape have focused on enhancing cooperation in the Indian Ocean.[i],[55] Additionally, the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), a sub-regional organisation in the Bay of Bengal region, has sought to address maritime security issues to some extent through its Expert Group on Maritime Security Cooperation.[56]

None of these initiatives, however, have been meaningfully instrumental in shaping a broader maritime security architecture in the Indian Ocean. The effectiveness of minilateral groupings in fostering regional maritime security cooperation is limited for various reasons. First, these groupings involve countries often geographically proximate to each other, restricting their scope of cooperation to specific areas with limited implications for the wider strategic theatre. Second, as the Indian Ocean region is divided into sub-regions, minilateral groupings tend to be subsumed within constructs of these sub-geographies.[j],[57] Third, regional maritime security architectures must emphasise on fostering regional consciousness of common challenges. Minilateral groupings, however, tend to operate on issue-based variables, instead of emphasising on geography.

The Limitations of Maritime Security Cooperation in the Indian Ocean

Efforts to construct a coherent maritime security architecture in the Indian Ocean face significant challenges due to evolving geopolitical context. Security interests and their framing are shaped by geopolitical choices, leading to a lack of political unity among Indian Ocean littorals.[58] This arises from differing strategic compulsions, the absence of consensus on identifying maritime security threats, and insufficient synergy in collaborative efforts to address these issues. Moreover, the vast geographic expanse of the Indian Ocean contributes to a lack of regional consciousness among its littoral states. In this context, political unity entails a normative acknowledgement of the need to foster a pan-Indian Ocean regional consciousness based on a shared maritime expanse.

Such regional consciousness is impeded because most countries in the region identify themselves through other regional constructs. The Indian Ocean region encompasses countries that identify as South Asian, African, Southeast Asian, or West Asian. The vastness of the Indian Ocean contributes to diverse[k] security dynamics within the region. Diverse challenges across different parts of the Indian Ocean have limited the success of efforts to create a coherent maritime security architecture.

Conclusion

The overall maritime security architecture in the Indian Ocean remains fragmented as a result of the profound impacts of evolving geopolitical dynamics in the region. Numerous actors in the Indian Ocean continue to pursue their own efforts and strategies, which hinders meaningful cooperation. Although institutional arrangements such as IORA and IONS are in place, they have achieved limited success in forging political unity or issue-based cooperation in tackling imminent maritime security challenges in the Indian Ocean.

Some recommendations that may be useful in constructing a cohesive maritime security architecture in the Indian Ocean are as follows. First, it is important to foster a regional consciousness of the Indian Ocean as a singular political construct where all regional littoral states are key stakeholders. Second, promoting meaningful synergy in cooperation by focusing on common concerns. Although the region is vast, with varying challenges in different sub-regions, common issues such as rising sea levels, climate change, and illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing threaten to spill over across sub-regions. Addressing these common challenges could foster greater regional unity.

Third, institutional mechanisms need to be strengthened more. The maritime security dimension of IORA’s agenda needs to be heightened, as any effective strategy to tackle maritime challenges would require geopolitical convergence. Threats, risks, and challenges in the Indian Ocean continue to proliferate, and advancing discussion on opportunities for cooperation is essential in order to build a cohesive maritime security architecture in the region.

source : orfonline