search the site

ASEAN:Overcoming the Continental-Maritime Divide

By Kwa Chong Guan 12 ctober 2023

SYNOPSIS

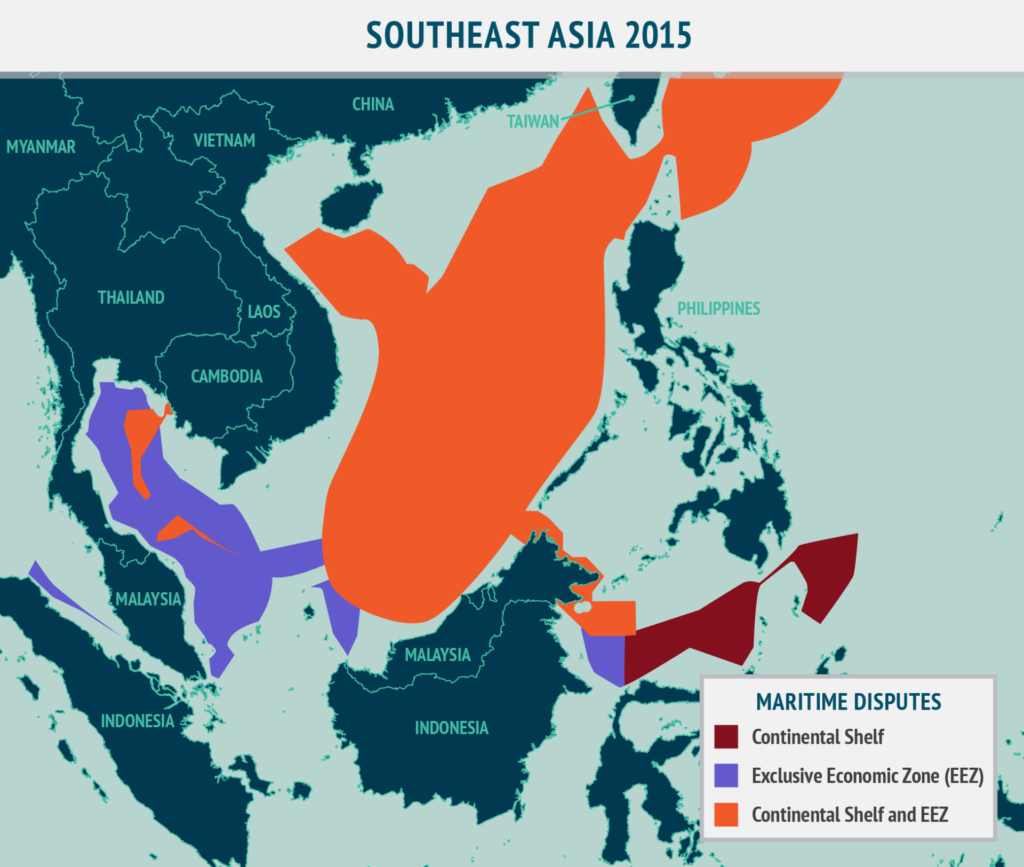

The expansion of ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) in the 1990s brought together its founding members, a group of countries located in the maritime world of Southeast Asia, with the other countries on the mainland of the region centred around the major river systems (notably the Irrawaddy and Mekong). The growth of ASEAN conjoined two sets of modern states with divergent socio-cultural upbringing and geopolitical visions: one dependent on the seas around it and the other on the great rivers and their headwaters upon which their livelihood depended. ASEAN’s disunity and indecisiveness on critical issues it faces in the South China Sea and major power competition in the region is in part a consequence of this geographical reality.

COMMENTARY

ASEAN’s critics have had a field day over the Association’s 43rd Summit failure to respond to the crisis in Myanmar, China’s new national map reiterating its claim to the South China Sea, and the impact of US-China competition and tension among other issues confronting the region.

ASEAN is seen to be disunited and indecisive. In part, this is a consequence of ASEAN’s success as an institution, especially since the end of the Cold War when ASEAN successfully positioned itself as central to the emerging post-Cold War regional architecture, and as such, expected to be more united and decisive.

An Island World reacting to developments on its Continental North

It may however be relevant to reflect that ASEAN’s beginnings in 1967 were far more modest: to bring Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia together in a new relationship after the end of the Indonesian Confrontation of Malaysia and to find a way for Malaysia and the Philippines to manage the latter’s claims to Sabah. ASEAN for its first decade was a forum for its foreign ministers to discuss their relations with each other.

ASEAN’s first wake-up call was North Vietnam’s conquest of South Vietnam and the Khmer Rouge takeover of Cambodia in 1975. The non-Communist members of ASEAN were now confronted by Communist “tigers” in its backyard while they were fighting local Communist parties waging People’s Wars in Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines and Thailand, and Indonesia was still purging itself of remnants of the Indonesian Communist Party from its body politic.

ASEAN convened its first Heads of Government meeting in Bali in 1976 to consolidate its response to this growing Communist threat. A more urgent wakeup call came in 1979 when the Vietnamese army went into Cambodia and ASEAN’s founding leaders woke up to the reality that the Communist tiger in its backyard was now at their backdoor.

ASEAN supported the formation of a Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK) to oppose the Vietnamese occupation of Cambodia and helped defend CGDK’s right to Cambodia’s seat at the United Nations over the next decade. ASEAN emerged from the Cold War with its political and diplomatic credentials enhanced, and confident of playing a major post-Cold War role in Southeast Asia.

ASEAN moved to bring its ten Dialogue Partners to form an ASEAN Regional Forum in 1994 to build confidence and trust as the foundation for the building of preventive diplomacy structures in the region. More significantly, ASEAN opened up its membership to the mainland Southeast Asian countries of Vietnam in 1995, Laos and Myanmar in 1997, and Cambodia in 1999.

This expansion of ASEAN’s membership to include all the territories south of China and east of India culminated in the localisation of a World War II Allied Command designation of these territories as a theatre of war which excluded the Philippines. The latter was, as a US colony, assigned to the US Pacific Ocean theatre.

Before that, Southeast Asia was the domains of Dutch, British, and French colonial empires encompassing two different worlds: a maritime world of the Dutch East Indies, the Philippines, and British Malaya with the Borneo territories of Sabah, Brunei and Sarawak, and a continental world of French Indochina, British Burma, and Siam (modern-day Thailand).

An Island and a Continental Southeast Asia Divide

It is the seas which define and connect the archipelagos of maritime Southeast Asia. Sea lanes, on which the coastal communities sailed and traded, crisscrossed these seas linking southern Chinese ports with ports on the Indian subcontinent and with ports in the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. Maritime trade in spices and other tropical products was the foundation of the major kingdoms of Sriwijaya in South Sumatra, Sailendra in central Java, Majapahit in east Java and Melaka on the Malay Peninsula.

The historic kingdoms of mainland Southeast Asia were however defined by the great rivers on the plains on which they were located. Angkor was built on the plains of the Tonle Sap Lake which feeds on the Mekong River. The Vietnamese kingdoms of the Ly, Tran and Le dynasties were shaped by the Red River. The Thai kingdom of Sukhothai and its successor Ayutthya were located on Chao Phraya River. Bagan and its successor kingdoms of Ava and Konbaung were established on the upper reaches of the Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy) River, while Bagu was established in the lower reaches of the Ayeyarwady.

In 2005, the Myanmar government decamped the eighteenth-century port city of Rangoon, which the British had developed into the administrative capital of British Burma and which continued to serve as Myanmar’s capital since independence in 1948. The Myanmar government relocated their capital, named Naypyidaw, inland to Pyinmana in the dry zone heartland of the country, and from where, presumably they could gaze at their inland frontiers better than at Rangoon.

The gaze of all the mainland Southeast Asian kingdoms was not south to the sea, but north, to the headwaters of the great rivers which they depended upon. Imperial China weighed more heavily on continental Southeast Asia than on maritime Southeast Asia.

The founding members of ASEAN were the maritime countries of Southeast Asia and included Thailand as the Association was a continuation of an earlier Association of Southeast Asia (ASA) set up in 1961 between Malaya, the Philippines and Thailand as an alternative regional approach to regional security from the US-backed Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO).

The expansion of ASEAN in the 1990s to include the mainland countries of the region was in a way perceived as fulfilment of ASEAN as a regional association of all the countries of “Southeast Asia”. But in adopting this World War II Allied demarcation of a theatre of military operations – inevitable in the post-World War II politics of regionalism – ASEAN has also inherited not only diverse, but divergent geopolitical framings of the region south of China and east of India.

Resilience of ASEAN

The challenge for ASEAN today is to bring more convergence to these historical and geopolitical divergences within the Association as current geopolitical forces pull the continental half and the maritime half of the Association to look at different futures, with continental ASEAN looking more northwards to the headwaters of its river systems and maritime ASEAN looking to the future in the seas around it.

The “Masterplan on ASEAN Connectivity 2025” to achieve a seamless and comprehensively connected and integrated ASEAN is a major step towards bringing more convergence between ASEAN’s diverse members as is the ASEAN Community Vision 2025. These visions and masterplans provide the institutional framework to integrate ASEAN’s diverse members. There is recognition that a resilient ASEAN will be the way forward though every member state will need to be dragged along at one time or another by a specific exigency felt at the national level.

The challenge is whether the geopolitical mindset of ASEAN member states is responding to ASEAN’s institutional visions and plans fast enough. The current approach of political expediency and consensus-based decision-making in ASEAN is no longer adequate to deal with the rapidly changing dynamics among major powers impinging on ASEAN interests in an increasingly digitalised and technology-driven global order threatened by a severe climate crisis. The survival instincts demonstrated by ASEAN leaders in the first few decades of the organisation will be germane and instructive.

Kwa Chong Guan is a Senior Fellow at S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore. He co-chairs Singapore’s membership at the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific (CSCAP). He has an Honourary Adjunct position at the History Department of the National University of Singapore and is an Associate Fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

ASEAN:

Overcoming the Continental-Maritime Divide

By Kwa Chong Guan

SYNOPSIS

The expansion of ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) in the 1990s brought together its founding members, a group of countries located in the maritime world of Southeast Asia, with the other countries on the mainland of the region centred around the major river systems (notably the Irrawaddy and Mekong). The growth of ASEAN conjoined two sets of modern states with divergent socio-cultural upbringing and geopolitical visions: one dependent on the seas around it and the other on the great rivers and their headwaters upon which their livelihood depended. ASEAN’s disunity and indecisiveness on critical issues it faces in the South China Sea and major power competition in the region is in part a consequence of this geographical reality.

COMMENTARY

ASEAN’s critics have had a field day over the Association’s 43rd Summit failure to respond to the crisis in Myanmar, China’s new national map reiterating its claim to the South China Sea, and the impact of US-China competition and tension among other issues confronting the region.

ASEAN is seen to be disunited and indecisive. In part, this is a consequence of ASEAN’s success as an institution, especially since the end of the Cold War when ASEAN successfully positioned itself as central to the emerging post-Cold War regional architecture, and as such, expected to be more united and decisive.

An Island World reacting to developments on its Continental North

It may however be relevant to reflect that ASEAN’s beginnings in 1967 were far more modest: to bring Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia together in a new relationship after the end of the Indonesian Confrontation of Malaysia and to find a way for Malaysia and the Philippines to manage the latter’s claims to Sabah. ASEAN for its first decade was a forum for its foreign ministers to discuss their relations with each other.

ASEAN’s first wake-up call was North Vietnam’s conquest of South Vietnam and the Khmer Rouge takeover of Cambodia in 1975. The non-Communist members of ASEAN were now confronted by Communist “tigers” in its backyard while they were fighting local Communist parties waging People’s Wars in Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines and Thailand, and Indonesia was still purging itself of remnants of the Indonesian Communist Party from its body politic.

ASEAN convened its first Heads of Government meeting in Bali in 1976 to consolidate its response to this growing Communist threat. A more urgent wakeup call came in 1979 when the Vietnamese army went into Cambodia and ASEAN’s founding leaders woke up to the reality that the Communist tiger in its backyard was now at their backdoor.

ASEAN supported the formation of a Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK) to oppose the Vietnamese occupation of Cambodia and helped defend CGDK’s right to Cambodia’s seat at the United Nations over the next decade. ASEAN emerged from the Cold War with its political and diplomatic credentials enhanced, and confident of playing a major post-Cold War role in Southeast Asia.

ASEAN moved to bring its ten Dialogue Partners to form an ASEAN Regional Forum in 1994 to build confidence and trust as the foundation for the building of preventive diplomacy structures in the region. More significantly, ASEAN opened up its membership to the mainland Southeast Asian countries of Vietnam in 1995, Laos and Myanmar in 1997, and Cambodia in 1999.

This expansion of ASEAN’s membership to include all the territories south of China and east of India culminated in the localisation of a World War II Allied Command designation of these territories as a theatre of war which excluded the Philippines. The latter was, as a US colony, assigned to the US Pacific Ocean theatre.

Before that, Southeast Asia was the domains of Dutch, British, and French colonial empires encompassing two different worlds: a maritime world of the Dutch East Indies, the Philippines, and British Malaya with the Borneo territories of Sabah, Brunei and Sarawak, and a continental world of French Indochina, British Burma, and Siam (modern-day Thailand).

An Island and a Continental Southeast Asia Divide

It is the seas which define and connect the archipelagos of maritime Southeast Asia. Sea lanes, on which the coastal communities sailed and traded, crisscrossed these seas linking southern Chinese ports with ports on the Indian subcontinent and with ports in the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. Maritime trade in spices and other tropical products was the foundation of the major kingdoms of Sriwijaya in South Sumatra, Sailendra in central Java, Majapahit in east Java and Melaka on the Malay Peninsula.

The historic kingdoms of mainland Southeast Asia were however defined by the great rivers on the plains on which they were located. Angkor was built on the plains of the Tonle Sap Lake which feeds on the Mekong River. The Vietnamese kingdoms of the Ly, Tran and Le dynasties were shaped by the Red River. The Thai kingdom of Sukhothai and its successor Ayutthya were located on Chao Phraya River. Bagan and its successor kingdoms of Ava and Konbaung were established on the upper reaches of the Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy) River, while Bagu was established in the lower reaches of the Ayeyarwady.

In 2005, the Myanmar government decamped the eighteenth-century port city of Rangoon, which the British had developed into the administrative capital of British Burma and which continued to serve as Myanmar’s capital since independence in 1948. The Myanmar government relocated their capital, named Naypyidaw, inland to Pyinmana in the dry zone heartland of the country, and from where, presumably they could gaze at their inland frontiers better than at Rangoon.

The gaze of all the mainland Southeast Asian kingdoms was not south to the sea, but north, to the headwaters of the great rivers which they depended upon. Imperial China weighed more heavily on continental Southeast Asia than on maritime Southeast Asia.

The founding members of ASEAN were the maritime countries of Southeast Asia and included Thailand as the Association was a continuation of an earlier Association of Southeast Asia (ASA) set up in 1961 between Malaya, the Philippines and Thailand as an alternative regional approach to regional security from the US-backed Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO).

The expansion of ASEAN in the 1990s to include the mainland countries of the region was in a way perceived as fulfilment of ASEAN as a regional association of all the countries of “Southeast Asia”. But in adopting this World War II Allied demarcation of a theatre of military operations – inevitable in the post-World War II politics of regionalism – ASEAN has also inherited not only diverse, but divergent geopolitical framings of the region south of China and east of India.

Resilience of ASEAN

The challenge for ASEAN today is to bring more convergence to these historical and geopolitical divergences within the Association as current geopolitical forces pull the continental half and the maritime half of the Association to look at different futures, with continental ASEAN looking more northwards to the headwaters of its river systems and maritime ASEAN looking to the future in the seas around it.

The “Masterplan on ASEAN Connectivity 2025” to achieve a seamless and comprehensively connected and integrated ASEAN is a major step towards bringing more convergence between ASEAN’s diverse members as is the ASEAN Community Vision 2025. These visions and masterplans provide the institutional framework to integrate ASEAN’s diverse members. There is recognition that a resilient ASEAN will be the way forward though every member state will need to be dragged along at one time or another by a specific exigency felt at the national level.

The challenge is whether the geopolitical mindset of ASEAN member states is responding to ASEAN’s institutional visions and plans fast enough. The current approach of political expediency and consensus-based decision-making in ASEAN is no longer adequate to deal with the rapidly changing dynamics among major powers impinging on ASEAN interests in an increasingly digitalised and technology-driven global order threatened by a severe climate crisis. The survival instincts demonstrated by ASEAN leaders in the first few decades of the organisation will be germane and instructive.

Kwa Chong Guan is a Senior Fellow at S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore. He co-chairs Singapore’s membership at the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific (CSCAP). He has an Honourary Adjunct position at the History Department of the National University of Singapore and is an Associate Fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.