search the site

Accidents related to ISM Code failures: What we have learned so far

Accidents related to ISM Code failures: What we have learned so far – SAFETY4SEA

Credit: Shutterstock

Implementation of the ISM Code offers the opportunity for the industry to move away from a culture biased towards blame to one of shared sense of personal responsibility for safety throughout the organisation. A major benefit of the ISM Code is that it encourages lessons to be learned from incidents.

Casualties | 14/06/19

In the following table, we have compiled a list of accidents related to ISM Code failures to highlight lessons learned. Besides, by learning lessons, safety procedures can be reviewed and amended to reduce risk of occurrence.

Herald of Free Enterprise: A wake-up call for Ro-Ro safety – SAFETY4SEA

Herald of Free Enterprise: A wake-up call for Ro-Ro safety

32 years have passed since the capsizing of Herald of Free Enterprise, only a few minutes after leaving the Belgian port of Zeebrugge on the night of 6th March 1987, killing 193 people onboard. To date, the incident is considered, not only as the deadliest casualty involving a UK-registered ship since 1919, but also as a wake-up call for several safety improvements in this type of vessels. In addition, this catastrophic capsizing became the cause in 1987 for the IMO Assembly to develop the International Safety Management (ISM) Code and for the creation of UK MAIB.

Maritime Knowledge | 25/04/19

Accident details: At a glance

- Type of accident: Capsizing

- Vessel(s) involved: Herald of Free Enterprise (RoRo Vessel)

- Date: 6 March 1987

- Place: Port of Zeebrugge

- Fatalities: 193

- Pollution: No significant environmental pollution was reported.

Read in this series

- Learn from the past: Costa Concordia disaster

- Learn from the past: Bow Mariner incident

- Learn from the past: Exxon Valdez incident

- Learn from the past: The Princess of the Seas deadly sinking

- Learn from the past: Deepwater Horizon oil spill

- Learn from the past: Fire on board car carrier “Eurasian Dream”

- Learn from the past: MV Rena grounding

- Learn from the past: Prestige sinking, one of the worst oil spills in Europe

- Learn from the past: Erika oil spill, Europe’s environmental disaster

- Learn from the past: Ocean Ranger: Commemorating North America’s offshore disaster

- Learn from the past: Superferry14: The world’s deadliest terrorist attack at sea

- Learn from the past: Stellar Daisy sinking: Two years on and what?

- Learn from the past: Moby Prince: Italy’s worst maritime disaster since World War II

- Learn from the past: Sea Diamond: A pollution “bomb” at the bottom of Aegean Sea

- Learn from the past: Sewol sinking: South Korea’s ferry disaster

- Learn from the past: MT Haven: The worst oil spill ever in the Mediterranean

- Learn from the past: Herald of Free Enterprise: A wake-up call for Ro-Ro safety

- Learn from the past: Cougar Ace: How improper ballast water exchange can prove costly

- Learn from the past: Harvest Caroline: A case study on improper safety management

- Learn from the past: Bourbon Dolphin: A tragic example of ISM non-compliance

- Learn from the past: Pasha Bulker beaching: A mix of poor SMS, fatigue and bad weather

- Learn from the past: Viking Islay enclosed space fatalities: Rescuers becoming victims

- Learn from the past: Cosco Busan: Lack of communication, poor oversight and 53,500 gallons of oil in San Francisco Bay

- Learn from the past: MS Oliva grounding: Oil spill in one of the world’s most remote areas

The incident

In the afternoon hours of the 6th March 1987, the UK-registered Ro-Ro ferry ‘Herald of Free Enterprise’ sailed in the inner harbor at Belgium’s Port of Zeebrugge, with 80 crew members, 459 passengers, 81 cars, 47 freight vehicles and three other vehicles onboard.

Leaving for Dover, the ‘Herald’ passed the outer mole at 18.24. She capsized about four minutes later. During the final moments, the ferry turned rapidly to starboard and was prevented from sinking totally because her port side took the ground in shallow water.

The ‘Herald’ came to rest on a heading of 136″ with her starboard side above the surface. Water rapidly filled the ship below the surface level trapping people inside the hull.

As a result, 193 people onboard (others say 188) lost their lives, mostly from hypothermia. Many others were injured.

Probable causes

The immediate factor that led Herald to capsize is that it went to sea with its inner and outer bow doors open, the official investigation report reads. Namely, key factors included:

–>Negligence: The assistant bosun has accepted that it was his duty to close the bow doors at the time of departure from Zeebrugge and that he failed to carry it out. While he had opened the bow doors on arrival in Zeebrugge, he went to his cabin after completing his tasks, where he fell asleep and was not awakened by the call announcement on the loudspeakers that the ship was ready to sail. He remained asleep on his bunk until he was thrown out of it when the HERALD began to capsize. Meanwhile, the First Chief Officer and the Captain also failed to check the doors were closed upon departure.

–>Poor communication and lack of directions: The official accident report highlighted that poor relationship between ship operators and shore-based managers contributed to the tragedy. In court hearings, an ambiguity became evident regarding the definition of each one’s duties and responsibilities.

It was the failure to give clear orders about the duties of the Officers on the Zeebrugge run which contributed so greatly to the causes of this disaster,

…the official report reads.

A company official admitted that, long before the 6th March 1987, both the company’s sea and shore staff should have given proper consideration to the adequacy of the whole system relating to the closing of doors on this class of ship with their clam doors.

If they had, they should, and would, have improved the system notably by first improving their instructions, at the very least by introducing in the Bridge and Navigation Procedures Guide an express instruction that the doors should be closed, secondly by introducing a positive reporting system, thirdly by ensuring that the closure of the doors was properly checked and, fourthly, by introducing a monitoring or checking system.

–>Pressure to leave the berth: A significant question on the aftermath of the incident was, why could not the loading officer remain on G deck until the doors were closed before going to his harbour station on the bridge? That operation could be completed in less than three minutes. However, it was revealed that the officers always felt under pressure to leave the berth immediately after the completion of loading.

–>Ship design: No. 12 berth at Zeebrugge was a single level berth, not capable of loading both E and G decks simultaneously, as at the berths in Dover and Calais for which the ship was designed. The ramp at Zeebrugge was designed for loading on to the bulkhead deck of single deck ferries. In order to load the upper deck of the HERALD, trim ballast tanks Nos. 14 and 3 were filled.

–>Squat Effect: Reports attribute the incident to a hydrodynamic phenomenon known as the Squat Effect. Under this phenomenon, a ship moving quickly in shallow water creates an area of lowered pressure, shifting the ship closer to the seabed than would otherwise be expected. This means that the water that should normally flow under the hull encounters resistance due to the close proximity of the hull to the seabed and the ship is pulled down.

Liability

Seven people involved at the company were charged with gross negligence manslaughter, and the operating company was charged with corporate manslaughter.

The case collapsed but it set a precedent for corporate manslaughter being legally admissible in an English court.

The Captain and Chief Officer were suspended from duty.

Lessons learned

A general culture of poor communication in the owner company was highlighted soon after the accident. In this respect, the Court stressed the need for:

- Clear and concise orders.

- Strict discipline.

- Attention at all times to all matters affecting the safety of the ship and those onboard. There must be no “cutting of corners”.

- The maintenance of proper channels of communication between ship and shore for the receipt and dissemination of information.

- A clear and firm management and command structure.

Additionally, shortly after the accident, the UK called IMO to amend SOLAS, 1974. Starting from April 1988, the MSC adopted SOLAS amendments, including among others:

- a new regulation requiring indicators on the navigating bridge for doors which, if left open, could lead to major flooding

- a new regulation requiring monitoring of special category and ro-ro spaces to detect undue movement of vehicles in adverse weather, fire, the presence of water or unauthorized access by passengers whilst the ship is underway.

- provision of supplementary emergency lighting for ro-ro passenger ships.

- the so-called “SOLAS 90” standard, relating to the stability of passenger ships in damaged condition.

- a new regulation requiring cargo loading doors to be locked before the ship proceeds on any voyage and to remain closed until the ship is at its next berth.

Notwithstanding the fact that several measures were taken following the accident, it cannot be ignored that a lot of fatalities would have been avoided if safety culture had been built into routine operational procedures.

Explore more by reading the official investigation report:

Did u know?

- The accident caused the highest death toll of any peacetime maritime disaster involving a British ship, since the sinking of HMY Iolaire on 1 January 1919 near Stornoway, where at least 205 perished of the 280 onboard.

- Film director Krzysztof Kieślowski was criticised for using footage of the disaster in his film ‘Three Colours: Red’, although it is unclear if he actually did.

- A stained-glass window at St Mary’s Church in Dover pays tribute to those who died on the Herald of Free Enterprise.

- Australian businessman Maurice de Rohan, who lost his daughter and son-in-law in the tragedy, founded Disaster Action, a charity which assists people affected by similar events.

- One of the outcomes of the investigation of this accident was the formation of UK MAIB in 1989.

Learn from the past: Exxon Valdez incident – SAFETY4SEA

Learn from the past: Exxon Valdez incident

March 24 marks the 29th anniversary of the Exxon Valdez accident. On this date in 1989, one of the most catastrophic – if not the most catastrophic – oil spills of the 20th century took place. The tanker Exxon Valdez was departing the Port of Valdez, Alaska with a full load of North Slope crude oil, of approximately 1.26 million barrels, destined for Long Beach when it grounded on Bligh Reef in Prince William Sound. About 258,000 barrels of cargo were spilled as eight cargo tanks ruptured, causing one of the most shocking environmental disasters in the history of US.

Casualties | 23/03/18 Read in this series

- Learn from the past: Costa Concordia disaster

- Learn from the past: Bow Mariner incident

- Learn from the past: Exxon Valdez incident

- Learn from the past: Deepwater Horizon oil spill

- Learn from the past: The Princess of the Seas deadly sinking

- Fire on board car carrier “Eurasian Dream”

- Learn from the past: MV Rena grounding

- Learn from the past: Prestige sinking, one of the worst oil spills in Europe

- Learn from the past: Erika oil spill, Europe’s environmental disaster

- Learn from the past: Ocean Ranger: Commemorating North America’s offshore disaster

- Learn from the past: Superferry14: The world’s deadliest terrorist attack at sea

- Learn from the past: Stellar Daisy sinking: Two years on and what?

- Learn from the past: Moby Prince: Italy’s worst maritime disaster since World War II

- Learn from the past: Sea Diamond: A pollution “bomb” at the bottom of Aegean Sea

- Learn from the past: Sewol sinking: South Korea’s ferry disaster

- Learn from the past: MT Haven: The worst oil spill ever in the Mediterranean

- Learn from the past: Herald of Free Enterprise: A wake-up call for Ro-Ro safety

- Learn from the past: Cougar Ace: How improper ballast water exchange can prove costly

- Learn from the past: Harvest Caroline: A case study on improper safety management

- Learn from the past: Bourbon Dolphin: A tragic example of ISM non-compliance

- Learn from the past: Pasha Bulker beaching: A mix of poor SMS, fatigue and bad weather

- Learn from the past: Viking Islay enclosed space fatalities: Rescuers becoming victims

- Learn from the past: Cosco Busan: Lack of communication, poor oversight and 53,500 gallons of oil in San Francisco Bay

- Learn from the past: MS Oliva grounding: Oil spill in one of the world’s most remote areas

How did the accident happen?

The US tankship Exxon Valdez had departed the Port of Valdez in Alaska, 1,263,000 barrels of crude oil, when it grounded on Bligh Reef in Prince William Sound, near Valdez, Alaska. At the time of the grounding, the vessel was under the navigational control of the third mate. No injuries, but 258,000 barrels of cargo were spilled resulting in catastrophic damage to the environment.

GET THE SAFETY4SEA IN YOUR INBOX!

Name:

Specifically, according to a report by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), the third mate and the master of Exxon Valdez were on the bridge, moments before the accident. The two men were discussing about the route of the ship, when the master told the third mate that he would leave the bridge for a little while. He also instructed him to inform him (the master) when the ship was about to return to the traffic lanes, leaving the third mate in charge of this.

A little later the third mate ordered a hard right, to return to the traffic lanes and informed the master, through a phone call. When the call ended the third mate noticed that the course of the vessel had not changed. Namely, he said that despite the fact that the ship was swinging right, the radar did not show that. After a few moments he called again the master telling him “I think we are in serious trouble”.

At the end of the call, the ship hit the bottom and it sustained a series of sharp jolts for about 10 seconds. The third mate then tried to steer left, but because of the hard right swinging, the vessel could not turn left. When the ship stopped, the third mate reported that he smelled gas and crude oil vapor.

About 258,000 barrels of cargo were spilled in the sea. The damage to the vessel was estimated at $25 million, the cost of the lost cargo at $3.4 million, and the cost of the clean-up of the oil spill at $1.85 billion.

Environmental Pollution

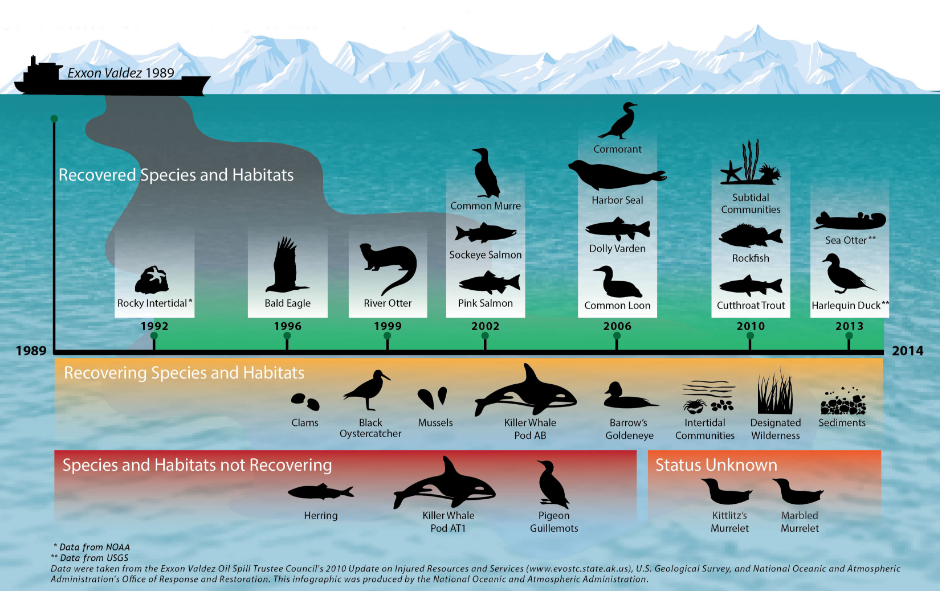

When the accident happened, Exxon Valdez was carrying approximately 55 million US gallons (210,000 m3) of oil, of which about 10.1 to 11 million US gallons (240,000 to 260,000 bbl; 38,000 to 42,000 m3) ended up in the Prince William Sound. This spill had an enormous effect on animals, the coastline and indigenous population:

- The amount of oil spilled could fill 125 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

- Immediate effects included the deaths of 250,000 seabirds, 2,800 sea otters, 12 river otters, 300 harbor seals, 247 bald eagles, 22 orcas, and an unknown number of salmon and herring.

- 1,300 miles of coastline were hit by the oil spill.

- The oil spill affected 11,000 square miles of ocean.

- The spill caused over $300 million of economic harm to more than 32 thousand people whose livelihoods depended on commercial fishing.

- Tourism decreased by 8% in south central Alaska and by 35% in southwest Alaska in the year after the spill.

- Twelve years after the spill, oil could still be found on half of the 91 randomly selected beaches surveyed.

The clean-up operations started shortly after the accident using booms and skimmers. However, not all of the equipment was available at the time, and the thickness of the oil damaged some of it. As a result, and despite the help that many volunteers offered, only 10% of total oil was actually completely cleaned. Namely, studies have shown that more than 26 thousand gallons (98 m3) of oil remain in the contaminated shoreline, declining at a rate of less than 4% per year. Until today, oil remains on the beaches and has the same chemical compounds as those it had 11 days after the incident.

Credit: NOAA

Investigation

When NTSB released the investigation about the accident, it focused on the failure of the third mate to maneuver the ship correctly, because of fatigue and excessive workload. The third mate could have had as little as 4 hours sleep before beginning work on March 23 and only a 1 to 2 hour nap in the afternoon. Thus, at the time of the grounding, he could have had as little as 5 or 6 hours of sleep in the previous 24 hours.

Another major issue is that the vessel did not have the proper amount of crewmembers working onboard. Evidence showed that watchkeeping safeguards on the Exxon Valdez were not on an appropriate standard because of the lack of crew.

The Safety Board considers the reduced manning practices of the Exxon Shipping Company generally incautious and without apparent justification from the standpoint of safety. The financial advantage derived from eliminating officers and crew from each vessel does not seem to justify incurring the foreseeable risks of serious accident.

Moreover, the investigation found that the company’s programs did not have measures in order to ensure the crew’s safety. In fact, NTSB concluded to the following:

- Absence of company programs to ensure that crewmembers observed 4 hours-of-service regulations;

- Lack of procedures to ensure that at least one rested deck officer, in addition to the master, was available for watch at departure;

- The practice of rating a crewmember’s performance according to willingness to work overtime, gave an incentive to work an excessive number of hours;

- Increase in workloads and standby time throughout the fleet before and after the grounding of the Exxon Valdez.

An interesting part of the investigation is the finding that the master failed to provide a proper navigation watch because of an alcohol problem. The master’s supervisor did not know that the master had an alcohol dependency problem before his hospitalization.

However, when the supervisor learned about this problem, he should have referred his case to the medical department. The personnel documents provided by Exxon showed that a follow-up treatment program was recommended by the attending physician at the hospital. The master was given a 90-day leave of absence, but there are no documents showing that the recommended treatment program was followed or that the master’s progress was monitored by the management.

Credit: European Climate Foundation

Recommendations

Concluding the report, NTSB made some recommendations to Exxon, as well as to the Alaska Regional Response Team. The recommendations to Exxon are the following:

- Eliminate personnel policies, including performance appraisal criteria, that encourage marine employees to work long hours without considering fatigue.

- Implement manning policies that prevent long working hours for crewmembers during cargo handling operations.

- Institute a policy forbidding deck officers to share navigation and cargo watch duties on a 6-hours-on, 6-hours-off basis, except in emergencies.

- Two licensed watch officers must be present to conn and navigate vessels in Prince William Sound.

- Implement an alcohol/drug program for seagoing employees that prevents such personnel from returning to sea until their alcohol/drug dependency problem is under control.

- Train persons in charge of the alcohol/drug rehabilitation program to use appropriate professional referrals, and improve skills necessary for competent rehabilitation supervision.

NTSB also recommended the Alaska Regional Response Team to develop clearer guides for dispersant use. This aimed to eliminate the need of a dispersant test before dispersants are used on an oil spill. The Alaska Regional Response Team should also include this information in the Alaska Regional Contingency Plan. Lessons Learned

The Exxon Valdez accident highlighted how important is the crew’s proper rest when operating a vessel.

- A proper resting period is vital for the safe operation of a vessel. Long working hours can be harmful for the crew’s ability to assess difficult situations correctly.

- An appropriate number of personnel onboard is crucial. This will make sure that crewmembers can have rest periods, and it will improve the operation of the ship in general.

- The vessels’ companies must be aware of the situation onboard a vessel, as well as their crew’s competency. If a company is aware of a crewmember’s dependency, it should help this member rehabilitate, and make sure that he/she is fit to be onboard a vessel after the rehabilitation.

- Shore staff must be well trained for situations of alcohol or drug dependency problems. The staff should know what needs to be done in order to, firstly, help the seafarer in need. Then they should make sure that this person is capable of working onboard a vessel again.

- An oil spill is catastrophic for the marine environment and extremely difficult to be cleaned. Many animals, the sea and even people felt the effects of the Exxon Valdez oil spill. What is more, because of the thickness of oil, its complete clean-up is almost impossible. As studies have shown, oil from the Exxon Valdez still affects some areas in Alaska. This highlights the importance for prevention measures, in order to reduce similar accidents in the future.

Below you can find the NTSB investigation report about the Exxon Valdez accident